Every night I write down six seconds of my day that I want to remember.

Some nights I struggle to come up with something worth writing down. That’s ok! Sometimes I’ll struggle for many days in a row. That’s less ok.

But when I have multi-day stretches where I have nothing to write down I notice. And noticing causes me to start changing my behavior. Journaling this way helps me seek out memories worth remembering.

Measuring and optimizing the right metric can be powerful. Measuring and optimizing the wrong metric can be disastrous. But sometimes the act of measurement itself is sufficient to change behavior for the better.

Waking up earlier and enjoying the morning more

Last month I wanted to change my sleep schedule.

I had spent much of the year rolling out of bed late and coding late into the night. But I’d just started attending the Recurse Center and part of the benefit of Recurse is getting to socialize with folks! And it’s a whole lot easier to socialize with others when you’re on similar schedules. My schedule at the time was something like “roll out of bed at 10:30, practice piano, exercise, eat lunch, and maybe make it to Recurse by 2 PM.” Not ideal.

But really I’d been meaning to change my sleep schedule for much of 2023 (it immediately shifted by several hours after I quit my job). In a fit of pique I added these events to my Google Calendar several months ago (they did not work, although they make me smile so I’ve kept them around).

I meant it in a loving way

So instead of force of will I turned to measurement. I made a simple Google Form with a few questions:

- When did I go to bed?

- When did I wake up?

- Was I tired when I woke up?

- When was I ready to do something (write code, see friends, etc)

- Did I play piano / exercise before starting to do something else?

I committed to non-judgmentally filling this form out every morning. And I waited.

And my behavior began to change! Some of these changes were relatively intuitive to me. I was more conscious of my bedtime and found myself saying “it’s past 1:00 AM, I’m not doing anything worthwhile, and my data will look better if I go to bed.”

But some of my behavior changes surprised me. I was more conscious of how I spent time in the morning, but also conscious of how I’m often not ready to do “hard” things immediately after waking up. Historically I’ve dealt with this by wasting time mindlessly browsing the internet which ~never makes me feel good. But quantifying how much time I’d spent on this each week pushed me to replace that time with something I enjoyed more. Often that was playing a game! Which isn’t a particularly productive activity - but swapping out “mindless browsing” for “playing a fun game” has consistently made my days more enjoyable.

I do track stats for 'time until I do something' but it isn't the point of this exercise.

And it’s that last bit that really stands out to me here. Observing how I spent the morning helped me find a change that made me substantially happier: but that change didn’t show up in the values I was measuring at all. If I’d been focused purely on optimizing “time until I do something in the morning” I might have missed this change entirely1!

Optimizing the wrong value can be dangerous - and one way to avoid that is to measure without optimizing at all.

Beware of accidental high scores

When I was in high school we had an internal email/forum called “SWIS” (School Wide Information System2, I think). As students we used the system to message each other, to message our teachers, to turn in homework, and to argue about nonsense in the “general student discussion” subforum. It was a key part of student life.

SWIS had two odd features:

- You could only stay logged in for 3 hours a day.

- It told you the total amount of time you had been logged into the system across your time at the school.

You can probably guess what happened. (we tried to boost our lifetime SWIS “log in time” as high as possible!)

It’s easy for measurements, especially aggregated measurements, to turn into high scores. And high scores can produce unexpected behavior. Sometimes that behavior is benign, or at least not obviously bad.

But high scores are easy (and fun!) to optimize. And that can lead you down the wrong path.

The internet is rife with horror stories about engineering management focusing on the wrong metric and, say, measuring productivity in lines of code. And of course it’s worth looking out for cases where you’ve simply chosen to optimize the wrong thing.

But more insidious, especially when you’re using the “measure and see” technique described in this post, is when you accidentally give yourself a high score that warps your behavior.

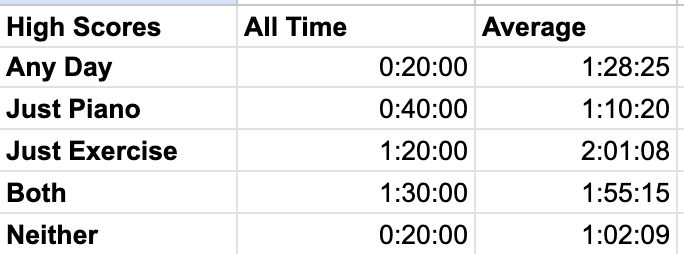

Earlier this year I began precisely measuring how much I was exercising in a given week. This wasn’t really because I was looking to change my behavior - it was just because I liked the stats that my Peloton gave me but I had started doing more non-Peloton exercise and didn’t want to feel bad about my numbers going down. I made a quick google form to track my workouts and whipped up a few aggregation functions.

the metrics I began tracking (all values are just 'time')

Pretty soon I was pushing myself to keep “exercise time this week” on par with or above “exercise time last week.” And to make that happen I began to cheat. I’d round up my estimates of the time I spent climbing. I was excited to include longer warmup and cooldown sessions in my workouts (alright maybe this one was good). And I began spending more time on exercise than actually made sense given my other goals.

Eventually I noticed what was going on and changed how I measured my behavior to be in more line with my actual goals. And I got rid of the high schore component entirely. But it took a month of unintentionally gunning for the wrong high score for me to catch on and adapt.

Sometimes measurement is enough

We know that measurement is powerful. You can’t improve what you don’t measure, and all that.

Sometimes that means carefully instrumenting a system and optimizing it along some wide range of metrics.

But just observing a value can change it. And sometimes that’s enough.

-

I suppose I could have pushed myself to rate the “fun-ness” of each morning, but that might have pushed me in a different direction and of course would have been much more qualitative and harder to measure. ↩

-

I accidentally brought SWIS down for a few days in my sophomore year. The system had powerful mail rules that let me write a rule that said “whenever I receive an email from myself send an email to my friend, send two emails to myself, and delete the email that I just got.” I set this up because a friend of mine got a loud “ding” every time he got an email and I thought it’d be funny to send him a flurry of emails. At some point I forgot to disable the rule before logging off and it ran overnight, sending millions of messages and crashing the system repeatedly for days. ↩

get new posts via twitter, substack, rss, or a billion other platforms

or subscribe to my newsletter right from this page!